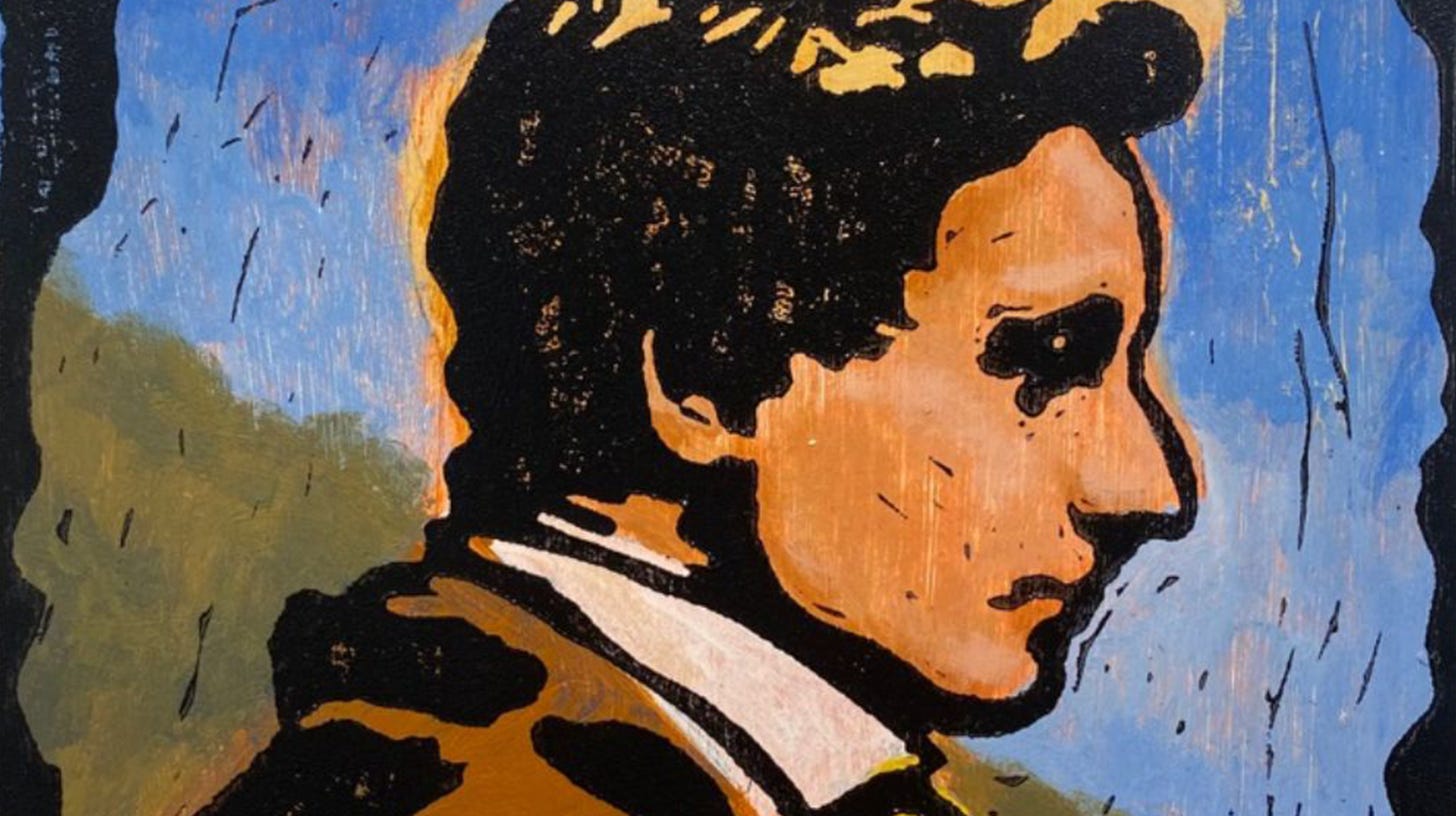

Latter-day Saints should love deconstructing. It's what Joseph Smith did

So why are we so scared of questions and doubts?

The Smiths were a part-member family.

In 1820, Lucy Mack Smith and three of Joseph’s siblings had joined a Presbyterian church. Joseph’s father was an avowed Universalist, but might not have belonged to any church at the time.

And while young Joseph was inclined toward the Methodists for a bit, he wasn’t committed. He didn’t dutifully show up every Sunday, and he didn’t trust everything that was said just because a pastor said it. If Joseph Smith was 15 years old today, and a member of our church, I can hear what we would say about him:

“He needs to doubt his doubts.”

“He probably got offended.”

“He’s not reading the scriptures and praying enough.”

“We need to get that boy on a mission.”

“Think of what he’s doing to his family.”

“He’s taking the easy way out.”

“He was led astray.”

As Latter-day Saints, we often look down on those who leave the Church (this shouldn’t be true, but it is). But those brave souls, whether you agree with their path or not, are following in Brother Joseph’s footsteps. Joseph Smith had questions, sought his own answers, and challenged everything. So why do we fear when Latter-day Saints do that now?

The term “deconstructing” comes up when people do what Joseph did. I really like this definition:

Faith deconstruction is the systematic taking apart of one’s belief system for examination.

I’ve seen it elsewhere defined as “the process of taking apart and examining an idea, tradition, practice, or belief to determine its truthfulness, usefulness, and impact.” For Latter-day Saints, this often means starting to split apart doctrine and culture. It means taking a specific belief—maybe a belief in the truth of the Book of Mormon, for example, or that prophets are called by God—and exploring whether it’s something you believe for yourself, or if it’s something where you’ve relied on the testimony of others. Or it might mean taking a specific practice—paying tithing, maybe, or worshipping in the temple—and deciding if it brings you closer to God.

In his various histories, Joseph Smith wrote about some of the things that troubled him as he deconstructed his youthful faith, in his search for truth—and now, two hundred years later, we’re still struggling with the same things. It’s almost uncanny to see the same questions he had echoed in those deconstructing their faith today. Here are a few:

“I don’t know what is true.”

That’s the whole First Vision story, right? Young Joseph Smith didn’t know what was true, and he wanted to find out. I think many of us, whether active in the Church or not, are joining Brother Joseph in asking, “Who of all these parties are right; or, are they all wrong together? If any one of them be right, which is it, and how shall I know it?”

It’s easy to assume that Joseph struggled to find truth because the Church hadn’t been restored yet. But more and more, I think the struggle to find truth is just part of being human in the first place.

“I don’t see Christ-like behavior in churches, or their leaders.”

Joseph Smith read the Bible, and didn’t see churches and their leaders doing the things that Christ taught. This is from his history, written circa 1832, writing about the time before the First Vision:

“Applying myself to [the scriptures], and my intimate acquaintance with those of different denominations, led me to marvel exceedingly. For I discovered that they did not adorn their profession by a holy walk and Godly conversation, agreeable to what I found contained in that sacred depository.” (edited for clarity)

It was true then and it is true now, no matter what church you’re talking about, because every church has human beings in it (including ours). Sometimes the pure teachings of Christ—to love our neighbor, to care for the marginalized—are lost amongst the administrative aspects of a global church organization.

“The world is just terrible.”

Is it surprising at all that Joseph Smith thought things were in pretty bad shape in the early 1800s? Isn’t that the quaint, pastoral lifestyle people want to go back to? This is what he said about it, also from his 1832 history:

“I pondered many things in my heart concerning the situation of the world of mankind: the contentions and divisions, the wickedness and abominations, and the darkness which pervaded the minds of mankind.” (edited for clarity)

Now, the shabby shape of the world may not be a reason to leave religion—it may actually spur people toward religion. But many people become disillusioned with the way their institutional church reacts (or doesn’t) to world events. Jesus Christ’s gospel is to lift the hands that hang down; this kind of one-to-one ministration isn’t always the hallmark of large organizations, churches or not. And as terrible as things are now—politically, socially, economically, whatever—they were bad in Joseph Smith’s time, too.

Deconstructing, asking questions, having doubts—Joseph Smith did all of these. And to us as Latter-day Saints, they were maybe the greatest things he could have done at the time. We celebrate that he asked questions, and for whatever reason, we panic when we have questions the same way he did.

But even when someone leaves the Church, they’re following the model that Joseph Smith set for us. Their faith journey is covered in the fingerprints of a gospel that encourages us to seek our own personal revelation. Asking questions is exactly what Joseph Smith did. Having doubts is exactly what he did, too.

It’s easy to say that Joseph Smith’s questions were rewarded with the First Vision, and our questions often get rewarded by nothing at all. I hear that, and I relate to it deeply. But while everyone’s experience with answers will be different, the process matters as much as the outcome. There is power in the asking.

The scripture verse that catalyzed the entire Restoration, James 1:5, is an invitation to recognize those deconstructing questions and take them to God. The assurance is that God is not judging us based on our questions; to me, this has a “there are no stupid questions” vibe. It’s clear that asking questions is not only okay, it’s recommended:

If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him.1

And, staying on the theme of verses that missionaries have memorized, Moroni’s promise says essentially the same thing. It says that if you want to know something, you should ask—don’t resist the question, don’t distrust yourself for having the question, but instead, just ask:

And when ye shall receive these things, I would exhort you that ye would ask God, the Eternal Father, in the name of Christ, if these things are not true; and if ye shall ask with a sincere heart, with real intent, having faith in Christ, he will manifest the truth of it unto you, by the power of the Holy Ghost.

And by the power of the Holy Ghost ye may know the truth of all things.

The problem with pulling out individual scripture verses to support this idea—that questions are key to a growing personal faith—isn’t that there are too few, it’s that there are too many. And beyond just verses, the scriptures are full of lengthy stories and narratives that deliver this same message over and over again. Here’s a few:

Alma’s treatise on faith in Alma 32 details exactly what we’re describing here. If you want to know if something is good or true, plant the seed by asking the question. In Alma’s parlance, maybe it will grow, maybe it won’t.

Gideon, in Judges 6, needed evidence from the Lord multiple times before he would believe. He just kept asking. I especially like in verse 39 where he says, “Let not thine anger be hot against me”—assuming that he’s pushing the limits of the Lord’s patience. The Lord answers anyway.

You could add in Nicodemus’s innocent questions for the Savior, Enos’s wrestle with God, the brother of Jared asking how to light the barges, etc. etc. All these people asked questions. So if we have questions, we’re in pretty good company.

Questions and doubts can be scary, in ourselves or others.2 Sometimes these questions are the outward manifestation of an inward existential grapple with our faith. Sometimes there is tremendous pain and loss behind these questions; that’s what happens when your whole identity, everything you’ve held close in your life, is suddenly in question.

I used to think that people who had questions and doubts were lacking faith. But now I realize that these are the people with the most faith—those who are making sense of the world in the face of everything falling apart. Having questions doesn’t mean losing faith. Doubting things that you were certain about before doesn’t mean losing faith. And even if your faith in the institution is on trial, you can still have a robust relationship with God.

Questions aren’t a sign of weak faith, they’re a sign of growing faith.

Elder Boyd K. Packer knew that the path forward isn’t always clear:

Somewhere in your quest for spiritual knowledge, there is that “leap of faith,” as the philosophers call it. It is the moment when you have gone to the edge of the light and stepped into the darkness to discover that the way is lighted ahead for just a footstep or two.

That’s the thing. Often, moving your faith forward means having to go right to the edge. You can’t hang back and expect the light to show you the way. We often assume that we can know everything in the gospel without paying the price to get there. The price we pay is going to the edge of what we know, putting our foot out, and seeing if there’s a place to step.

We see this in our culture, when we focus on how scripture stories end, rather than how they must feel in the middle. We skip over Jonah’s decision to not do what God asked and go to Ninevah, and instead just celebrate when he eventually does. We celebrate how none of Helaman’s stripling warriors died in battle, but we don’t think about the night before, when Helaman must have been sick with worry about what would happen to these young boys in a war of men. Similarly, we think all questions and doubts should just fast-forward to the happy ending, because of course there will be a happy ending.

Deconstruction can be hard on everyone involved. The person going through it is staring down a monumental shift in their life, one where they lose their once-beloved community. Their family is wondering if this is going to leave a metaphorical empty chair in the Celestial Kingdom. And the ward knows they’re supposed to be doing something, but they don’t know what.

In the Church, we lack the vocabulary and muscle memory to know how to be there for people whose faith is developing and evolving. We’re not good at it, the way we are at supporting someone who’s just had a baby or needs lunch organized for a funeral. You don’t really take a casserole to someone who is taking charge of their faith, someone who is working through the deconstruction, trying desperately to find the peace and harmony on the other side.

Right now, when we have questions, we feel like the only direction we can go is out of the Church. If everybody else’s faith appears to be rock-solid, while yours is crumbling, it’s natural to assume you don’t belong. Instead, we can talk openly about the questions we have, be vulnerable instead of putting up façades, and make space for every flavor and color of faith. If we normalized having questions, then others might recognize that staying-with-questions is an option too.

That’s what our church is about—or it should be. We believe deeply in personal revelation. We believe that when we ask, we can receive. We value, maybe more than anything else, our ability to have our own testimony and not have to take anyone’s word for it. The fact that we can know for ourselves, through honest questions, is at the heart of everything. Culturally, we can be scared of having questions. Whether it’s for ourselves or others, we wish we could just know, without going through the hard part.

But in a Church founded on a young boy’s questions, we should give people room to have questions.

I’ve used the familiar KJV version here—it can be jarring to use a different translation when generations of Latter-day Saints have recited this verse the same way. But read the NRSVue version too, and see if you get something useful out of it: “If any of you is lacking in wisdom, ask God, who gives to all generously and ungrudgingly, and it will be given you.”

Some people seem to get a bang out of drawing a difference between having questions and having doubts. The general idea is that questions are good, and doubts are bad. I don’t find this distinction to be useful. What if I have several questions and several doubts? Are my doubts okay if I phrase them as questions? What about concerns, are they good or bad? What about worries? Apprehensions? Misgivings?

I’ve even seen questions get split into primary questions and secondary questions, which suggests that we’ve jumped the shark on this pedantry.

Jesus also advocated against the institutional church of his time. Somehow I don't think this is what our leaders expect when they tell us to follow Christ

Thank you for this piece, Roger. This resonates strongly with my experience. As someone who has wrestled deeply with questions of my faith I never wanted the fact that I was wrestling cause me to be seen as a pariah who should not be supported in the full arms of loving fellowship (just as that was what I was needing and craving). I have so much more empathy now for others who wrestle with these issues, and although I've learned that my path is not necessarily theirs, I can sit with them in their struggle and be a loving and listening ear to validate their journey.