You can't earn God's love, because you can't earn what you already have

The thing I needed most, growing up in the Church, was a hug.

As a kid, I did all my homework, I attended all my youth activities, I went to seminary. I took girls on dates as a teenager but didn’t have a girlfriend until after my mission. I didn’t smoke or drink or do drugs—I didn’t even drink caffeine. And as previously discussed, I did not watch R-rated movies.

I did these things because I was a Good Kid. That was my identity; it’s who I was. My perceived value came from being Good. If I wasn’t Good, then I wasn’t anything at all. And that meant I was always in pursuit of being Better, so that I could continue to be worth something. If there was a way to earn love and approval, whether my parents’ or God’s, I was going to find a way to do it.

Maybe this was you growing up, and maybe this is you right now. Maybe you’re reading this, and you’re just so tired. Maybe you’ve been trying so hard. I see you, and I feel you, because I have been, too.

I remember one time, when I was five years old and in kindergarten, I had to “change my color” at school. Does this sort of thing still exist? You started every day with a green piece of construction paper in your paper slot on the wall. If you misbehaved in some way, the green paper would be taken out and you’d be down to the next color, yellow.1

The day I got bumped to yellow is still fresh in my mind, decades later. Not because of what I did, but because of the shame I felt associated with it. On the bus ride home that day, I crumpled the piece of yellow paper and discreetly tossed it under the plasticky brown bus seat. I did not take it home. I could not bear showing it to my parents.

The fact that I still carry this shame so long later, when it has long since stopped mattering, gives a sense of the merit-based way I viewed the world. I didn’t understand that my parents wouldn’t stop loving me because I’d been something other than perfect. I didn’t understand that parents really can and do love their children unconditionally.2

Now, as a parent, my children have made mistakes. I can tell you for sure that I loved them before the mistake, during the mistake, and after the mistake. So why is it so hard to understand that our Heavenly Parents love us before, during, and after every imperfect moment of our lives?

Clinical psychology and therapy have brought the language of attachment styles into our vernacular in recent years. I learned, one way or another, to have an anxious attachment with all the authority figures in my life. This is the attachment style embodied by insecurity about relationships, a need for reassurance, people-pleasing, and as a result of these things, low self-esteem. And while I don’t have any data to back this up, I think this is how many Latter-day Saints of my millenial generation grew up in relation to the Church.

Anxious attachment to God and the Church means you get to feel good on days where you read your scriptures, did your ministering, and lovingly cared for your kids. But it also means you have to feel bad on days you skipped the scriptures and ministering and yelled at your kids. And given how often we as mortals do the latter, we’d need to feel bad about ourselves a lot more than we feel good about ourselves.

You have to decide for yourself that you believe that God’s love is truly unconditional. If you go looking for scriptures and quotes that describe God’s love as conditional, you’ll find them3. But if you look for God’s love in your life, especially at the times you feel the least worthy of it, you’ll find that too. I think this is less a question of theology and more a question of what your relationship is with God.

Paul, in the New Testament, clearly believed in this unconditional love:

For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.

I’ll make plenty of space for Latter-day Saints who don’t see the Eternal this way. I didn’t, for a long time. The first question asked—always—is, well, if I am a recipient of God’s love and grace unconditionally, then does that mean I can do whatever I want? Does that mean I can just go sin?

The difference now is that I see this the opposite way. You could say that when we do what God asks, then He loves us. But I think, instead, that when we understand God’s love, we want to do what He asks. Take a moment and read those sentences again if you didn’t pick up the difference; it’s small, but meaningful. It’s “If ye love me, keep my commandments,” not “I’ll only love you if you keep my commandments.”

As Latter-day Saints, we’ve attached merit to every part of our worship. If you want to go to the temple, you have to meet certain criteria, like paying tithing. Joining the Church itself requires accomplishment; you have to have stopped smoking, etc. if you are to pass the missionaries’ baptismal interview and “qualify” to join the Lord’s church. And even when we talk about the atonement of Jesus Christ—the infinite sacrifice of an eternal being, that defeated sin and reconciled all of us in the eyes of God—we turn it into something that you have to do something to receive, something you have to “access” or “activate” in your life.

But that’s not what unconditional means.

Unconditional love finds me when I’ve climbed back into the safety of my bed, my face red from crying. Unconditional love finds me when I’ve messed things up, when it’s all my fault and I don’t know how to put it all back together. Unconditional love finds me on my worst days, the days when I don’t even love myself.

In the Church we sometimes talk about the difference between “worth” and “worthiness.” The idea is that everybody has inherent worth, but not everybody will be esteemed “worthy” to participate in temple ordinances, etc. I’ll just add one thing to that. The knowledge that we all have worth comes from an eternal concept; we were loved unconditionally in the pre-mortal life, we’re loved here in mortality, and we’ll continue to be loved after this life. Temple recommend interviews, as important as they are in today’s institutional Church, are not eternal. The Church concept of “worthiness” has a specific meaning, one that matters for a time and then will ultimately stop mattering. What matters on the eternal horizon is our individual worth, and that has never changed.

As Sister Tamara W. Runia said:

Obedience brings blessings; that is true. But worth isn’t one of them. Your worth is always ‘great in the sight of God,’ no matter where your decisions have taken you.

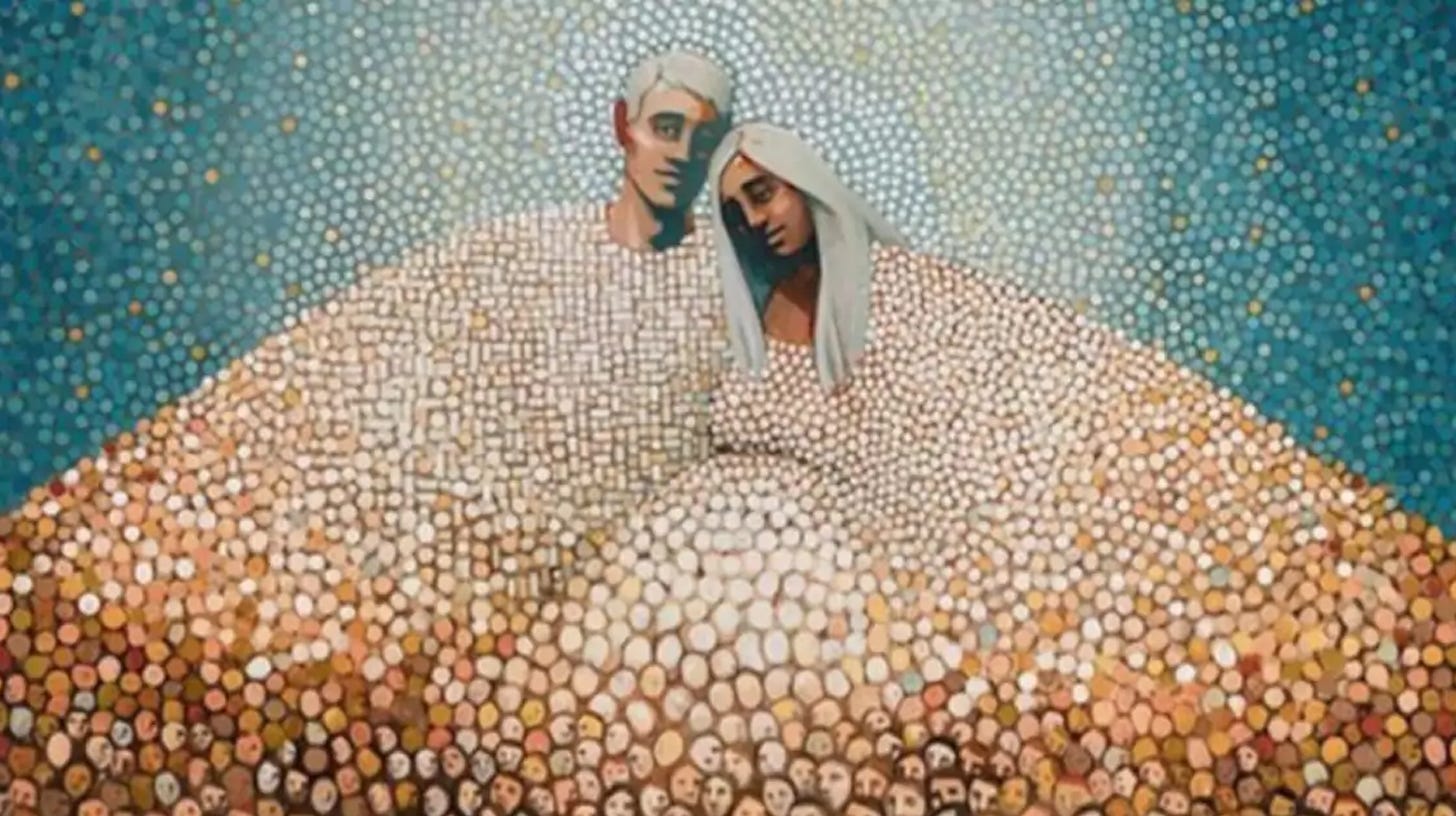

You can’t earn God’s love because you already have it. That’s the good news of the gospel. This infinite, eternal, and unconditional love surrounds you whether you see it or not. There is simply nothing you can do to earn more love, because there’s also nothing you can do to earn less.

You don’t have to believe it all the way for it to be true. You have Heavenly Parents who are watching you through everything you’re struggling with, rooting for you, and loving you through it.

Maybe, just for a moment today, you’ll be able to feel it.

I don’t remember what color came after yellow. I never got there.

Making space here for people who didn’t have loving parents. I am lucky enough to have top-notch parents, but I realize that is luck, and luck alone. It may be more challenging to reconcile the idea of loving Heavenly Parents if your earthly parents didn’t embody those virtues.

President Russell M. Nelson, while a member of the Twelve, famously described God’s love as “perfect, infinite, enduring, and universal,” but would not call it “unconditional.” I am not clear on the difference.

Thank you so much. This was beautiful.

You nailed it! Great article!